Langara's Anthropology Laboratory houses a collection of objects from Oceania, which were transferred to the college from the Kelowna Museums Society in 2019. This collection is used for teaching purposes and is used in our 'Museum Collections and Heritage' course. Click here for more information!

This page will be used to share information about the collection and the research that students have been undertaking with the objects. We are excited to share their research results with you, and look forward to additions and improvements to the page over time.

Most recently, in 2024, our Spring semester class created 3D models of some objects in the collection (along with other items in the anthropology lab). Check out the 3d models here: https://p3d.in/u/ANTH2220

Learn more about Oceania and the objects in our collection by clicking on the orange '+' signs (to the left of each section below)

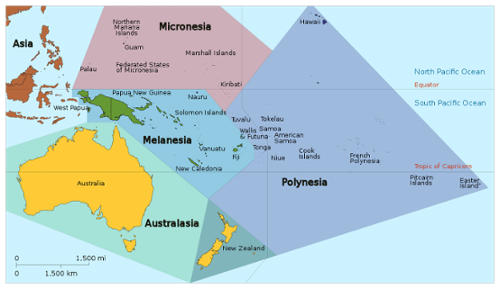

The objects in the Ethnographic Teaching Collection originate from Oceania: a geographic region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia (Map below: Oceanic_ISO_3166-1.svg by Tintazul on Wikipedia)

The majority of the objects originate from Melanesia, specifically Papua New Guinea. This is a region of the world that has long interested Anthropologists: Melanesia was one of the earliest regions outside of Africa to be settled by humans around 50,000 years ago. Today it is an incredibly culturally diverse region with more than 1200 languages spoken across the islands. Papua New Guinea is in fact the most linguistically diverse country in the world, where more than 800 languages are spoken! (Map below: Papua New Guinea, The World Factbook)

Students in ANTH 1195: Museum Studies have been learning about Oceania and Papua New Guinea in the course, including the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery

Length (including cord): 21cm, Width: 6cm, Thickness: 1cm

Research by Camille Yabut, Spring semester 2020

Originating from Papua New Guinea, this necklace is just one of many made from the shells of a cone snail. Due to the abundance of shells, jewelry made from shells is worn all over Oceania. Shell necklaces are commonly worn by men but may also be worn by women and children.

This specific necklace is made from the shell of a cone snail. Cone snail shells, otherwise known as conus shells, are a material commonly used in the jewelry of Papua New Guinea. The large range of shapes and sizes of cone snails allow for a large variety of pendants.

Left: Spirals of a fossilized cone snail shell. Right: A variety of cone snail shells, both fossilized and not (photos by James St. John, Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic, Flickr)

Shells also hold symbolic notations in Papua New Guinea. They are seen as a representation of culture and wealth, displaying the “status and achievements of their wearers” (Stewart and Strathern 2002, 137). Also, shells are traded amongst different groups and are a physical representation of the “ties and pathways of relationships between people” (ibid).

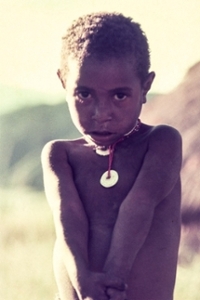

A young girl in Papua New Guinea wearing a shell necklace, much like the one in our collection (photo by John LeRoy, UC San Diego Library)

Many pendants showcase the natural beauty of the shells themselves. However, there are many different ways shells have been made into pendants. Some may be designed to be flat, much like the one in our collection. While others can be found painted, engraved or simply left as they are to showcase their natural colour and beauty. It is known that the delicate engravings and/or shaping were indicative of the fact that shell ornaments were valued artifacts (Ambrose et al. 2012, 121). Shell pendants often arose from a tedious shaping process. Shells are often “pounded and ground” (Lewis 1929, 10) into the desired shape with stones of various sizes and textures.

A variety of shell necklaces being worn during a sing-sing (photo by Gail Hampshire, Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic, Flickr)

Shell necklaces are often used as decoration, most often by men, around their necks for everyday use or during ceremonial occasions, such as a sing-sing, a traditional ritual dance that is often performed as a customary welcome for guests (Maeir 2015, 27).

Another important ceremony where shell necklaces are worn are malanggan feasts, a mortuary ceremony where the life of a deceased member of the community is honoured (Craig et al. 2015, 174). While there is no one singular definition for a malanggan, it is important to note that malanggan refers to “both certain ceremonial gatherings and for the carvings used in them” (Billings and Peterson 1967, 26). During malanggan ceremonies, along with festivities, “exchanges of shell currency” (ibid) are also featured with other gifts that may be exchanged and the “various ritual events [that are] added” (Billings and Peterson 1967, 27).

An example of a shell necklace deemed part of the “complex and heavily decorated” variety

(National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne)

Often, the more complex and heavily decorated necklaces belonged to those of higher status. These shells and pendants may also be used as a currency for exchange to purchase food, labor, and different crops (Stewart and Strathern 12002, 39). Shells, including but not restricted to cone shells, held monetary and exchange value.

Shell money was often came in the “form of small disks” (Lewis 9), much like the pendant in our collection, but smaller shells often came “arranged in strings” (Lewis 1929, 9). Their value as an exchange object draws importance in the fact that shells are worn and exchanged with others to “create relationships…and ultimately lead to further exchanges” (Stewart and Strathern 2002, 138). While shell currency is not as widely used as it once was, shells are still “used variously as forms of bodily adornment[s]” (Stewart and Strathern 2002, 141) such as, and not limited to, necklace pendants, “attached to the ears and ringlets of hair” (ibid).

I find there is such an indescribable beauty in the simplicity of this pendant. While I initially chose to do research on this necklace for its aesthetics, I was surprised to learn how much meaning such an ordinary object could hold. Upon first glance, one might glance over its simplicity and turn to a more heavily decorated pendant. I admit I was the same, however, after being given the opportunity to handle the pendant I was able to see the swirled indentations that were once hidden. I believe that a similar viewpoint can be said about the necklace. Despite its simplicity, it holds so much beauty and meaning that one might not be able to see upon first glance.

References

Ambrose, Wal, et al. 2012. “Engraved Prehistoric Conus Shell Valuables from Southeastern Papua New Guinea: Their Antiquity, Motifs and Distribution.” Archaeology in Oceania, vol. 47(3):113-132.

Billings, Dorothy K., and Nicolas Peterson. 1967. “Malanggan and Memai in New Ireland.” Oceania, vol. 38(1): 24-32.

Craig, Barry, et al. 2015. War Trophies or Curios? The War Museum Collection in Museum Victoria 1915-1920. Museum Victoria Publishing, Melbourne, Australia.

Lewis, Albert B. 1929. “Melanesian Shell Money: In Field Museum Collections.” Publications of the Field Museum of Natural History. Anthropological Series, vol. 19(1): i-36.

Maeir, Aren M. 2015. “A Feast in Papua New Guinea.” Near Eastern Archaeology, vol. 78(1): 26-34.

Stewart, Pamela J., and Andrew Strathern. 2002. “Transformations of Monetary Symbols: in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea.” L’Homme, no. 162: 137-156.

Height: 35cm Length: 25cm Width: 26cm Diameter: 14cm

Research by Gemma Biglowe, Spring semester 2020

This style of bowl is traditionally used by Abalem men to eat out of during ceremonial feasts, such as coming of age ceremonies for young men. For this reason, the most common way of decorating these bowls are with male faces surrounded by earth-toned geometric designs. Today these ceramic bowls are usually made to sell to tourists.

The Abelem people live in the East Sepik region of Papua New Guiney, which is on the North-Eastern side of the island. The region is known for producing a wide variety of beautiful ceramic works. The Abelem people usually source their clay from the Sepik river, and use natural materials to create the pigments used to decorate the vessels (May & Tuckson, 2000). Because this bowl is very similar in shape and design to other Kwam bowls made in this region, it is possible that the clay used to create this bowl may have come from the Sepik river.

Although the use and manufacture of Kwam bowls is generally reserved for men, the majority of ceramics produced by the Abelem people are made in collaboration between women and men (Rare Pottery, n.d.). Every step of the process is done by hand. Generally the women collect the clay, and form the shape of the bowl by coiling the clay (Rare Pottery, n.d.). This process involves rolling the clay into long ropelike sections, and then coiling them up until they form the desired shape. The bowls are then given to the men who refine the surface of the bowl (Rare Pottery, n.d.) and then crarve in the incized designs by using sticks, bone, animal teeth, or dried plant reeds (May & Tuckson, 2000). The bowls are given back to women to be fired (Rare Pottery, n.d.). The women ususally fire five or six bowls at a time, before returning them once again to the men for the final step: painting (May & Tuckson, 2000.; Rare Pottery, n.d.).

The up untill they form the desired shape. The bowls are then given to the men who refine the surface of the bowl (Rare Pottery, n.d.) and then crarve in the incized designs by using sticks, bone, animal teeth, or dried plant reeds (May & Tuckson, 2000). The bowls are given back to women to be fired (Rare Pottery, n.d.). The women ususally fire five or six bowls at a time, before returning them once again to the men for the final step: painting (May & Tuckson, 2000.; Rare Pottery, n.d.).

In recent years the majority of the ceramics produced in the region are for sale to the tourist market rather than for ceremonial purposes (May & Tuckson, 2000). Several examples of other types of Kwam ceremonial bowls that have been made by the Abalem people are on display in museums around the world. Such examples can be found in places like the British Museum, as well as in the Longyear Museum of Anthropology in New York State, who have examples of ceramics from Papua New Guinea as part of their University collection. There is also a very similar vessel on display right here in Vancouver at UBC's Museum of Anthropology (see image below)

Click here to see this object in MOA's online collection

References

Rare pottery from Papua New Guinea now on display at Longyear Museum. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.colgate.edu/news/stories/rare-pottery-papua-new-guinea-now-display-longyear-museum

May, P., & Tuckson, M. (2000). The Traditional Pottery of Papua New Guinea. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. https://books.google.ca/books?id=dBHkfjHE-i0C&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_ summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false